When you’re building a high-performance engine, every cubic centimeter of airflow matters. Porting a throttle body or intake manifold isn’t just a buzzword-it’s a real way to squeeze out more power. But not everyone understands what’s actually happening under the hood, or what you’re giving up in the process. If you’ve seen a dyno chart showing a 20-horsepower jump after porting, you might think it’s a free lunch. It’s not. There are tradeoffs you can’t ignore.

What Porting Actually Does

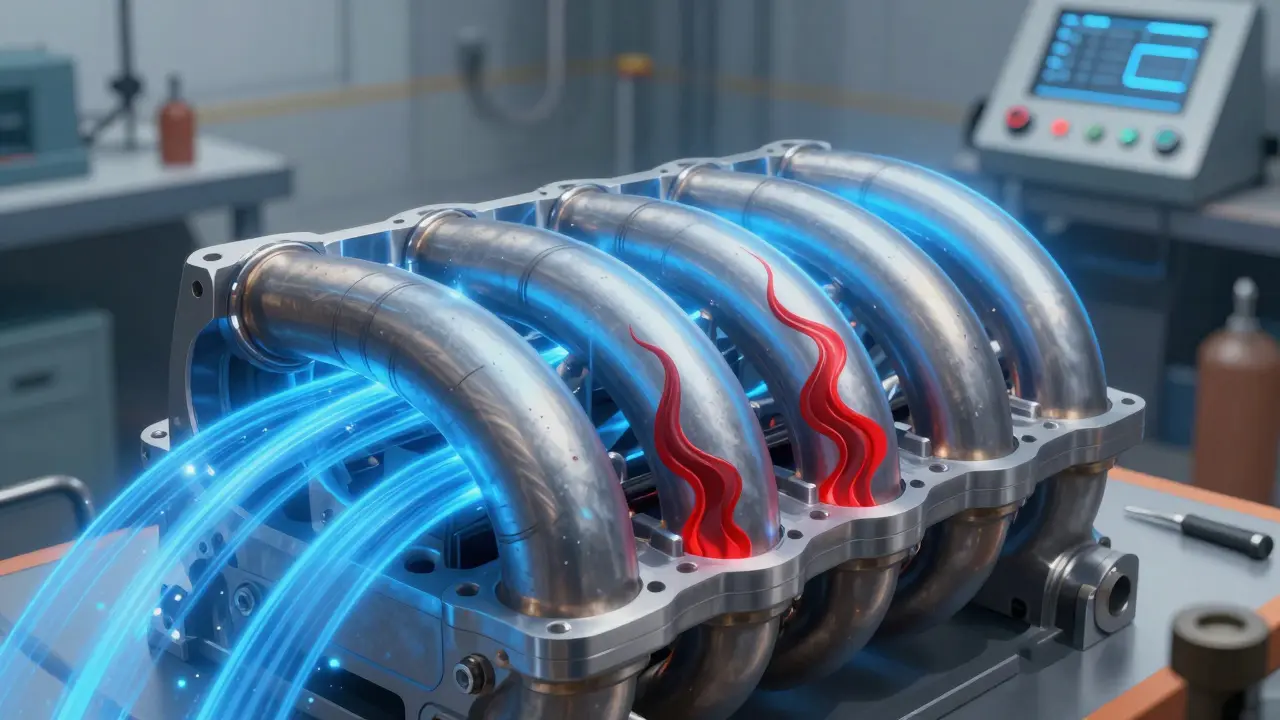

Porting means smoothing and reshaping the internal passages of a throttle body or intake manifold to reduce airflow resistance. Stock parts are designed for cost, durability, and emissions-not peak power. The inside of a factory intake often looks like a maze: rough cast surfaces, sharp corners, uneven walls, and narrow sections that choke airflow at high RPMs.

When you port it, you remove material to create a smoother, more direct path. Think of it like widening a highway from two lanes to four, removing potholes, and eliminating sharp turns. Air flows faster and more efficiently. That means more oxygen reaches the cylinders, which lets the engine burn more fuel and make more power.

Real-world gains? On a naturally aspirated 4-cylinder engine, a well-done port job on the throttle body can add 8 to 15 horsepower at the wheels. On a V8 with a stock intake manifold, porting the runners and plenum can net 15 to 30 horsepower-especially above 5,000 RPM. These aren’t guesses. They’re numbers from dyno tests on engines like the Ford Coyote, GM LS3, and Toyota 2GR-FSE, all modified by reputable shops like Edelbrock, Kinsler, and K&N.

Where the Gains Show Up

Porting doesn’t make your car faster everywhere. It’s a high-RPM tool. You’ll feel the difference most when you’re pushing the engine hard-on the highway, during passing maneuvers, or on a track day. At low speeds, like stop-and-go traffic or idle, you might not notice much change. Some people even report a slight drop in throttle response below 2,500 RPM.

Why? Because airflow velocity drops when you enlarge the passages too much. Air needs speed to stay mixed with fuel and fill the cylinder efficiently. Too much porting makes the air slow down, hurting low-end torque. That’s why professional porters don’t just make everything bigger-they shape the flow. They keep the throat of the throttle body tight for crisp response, then gradually widen the runners to maintain velocity until the engine needs maximum volume.

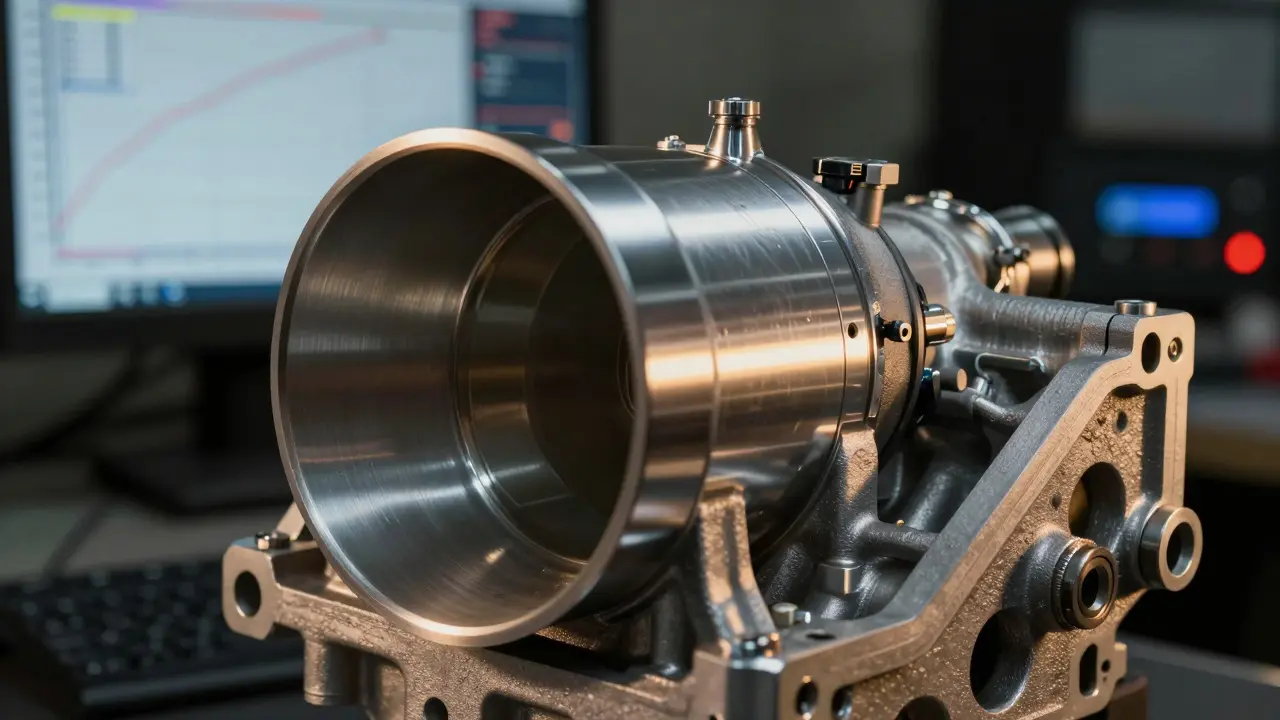

Take the Honda K20 engine. Stock throttle bodies are 62mm. A common upgrade is a 70mm unit, but without porting, the airflow doesn’t improve much because the internal walls are still rough. A ported 70mm throttle body, however, can flow 20% more air than the stock unit. That’s not magic-it’s physics.

Intake Manifold Porting: Bigger Isn’t Always Better

Intake manifolds are trickier. They’re not just tubes-they’re tuned chambers designed to create pressure waves that help pull air into the cylinders. This is called ram tuning. Stock manifolds are shaped to optimize torque across a broad range, not just peak power.

When you port an intake manifold, you’re changing its tuning. If you open up the runners too much, you lose low-end torque. If you make them too long or too short, you shift the power band. A well-portered intake for a 5.3L LS engine might gain 25 hp at 6,500 RPM but lose 12 lb-ft of torque at 3,000 RPM. That’s a net gain on the dyno, but in daily driving, you might feel like the car is sluggish off the line.

Some shops offer "performance" intakes that look flashy but are poorly designed. They use oversized runners that look impressive but hurt low-end response. Look for shops that show you flow bench data-numbers for airflow at 10 inches of water pressure across different RPM ranges. If they can’t show you that, they’re guessing.

The Hidden Costs

Porting isn’t cheap. A basic throttle body port job runs $250 to $400. A full intake manifold port, including balancing and polishing, can cost $800 to $1,500. And that’s just the labor. You might need new gaskets, bolts, or even a custom tune.

Here’s the catch: porting changes how the engine breathes. Your stock ECU is calibrated for the original airflow. After porting, the air/fuel ratio can go lean or rich, depending on how much more air you’re flowing. Without a proper tune, you risk engine damage. You might get a check engine light, rough idle, or even detonation under load.

Many people skip the tune because they think, "It’s just airflow-it should be fine." It’s not. A ported intake can increase airflow by 30% or more. The ECU doesn’t know that. It still thinks it’s dealing with the stock setup. That’s why a dyno tune after porting isn’t optional-it’s mandatory.

When Porting Makes No Sense

Not every engine benefits. If you have a stock turbocharged engine with a restrictive factory intake, porting might help. But if your car has a turbo or supercharger, the real bottleneck is often the compressor housing or intercooler-not the intake manifold. Porting the intake on a boosted engine without upgrading the turbo or intercooler is like putting a bigger straw on a clogged soda bottle.

Also, if your engine is heavily modified with big cams, high compression, or forced induction, porting becomes less impactful. At that point, you’re better off investing in a full aftermarket intake system designed for your setup. Companies like K&N, Kooks, and Kelford offer complete systems that are tuned from the ground up, not just modified stock parts.

Porting also doesn’t help if your engine has other issues. A leaking vacuum line, worn valve seals, or a weak fuel pump will mask any gains from porting. Fix those first. Porting isn’t a cure-all-it’s a fine-tuning step.

What to Look for in a Porting Shop

Not all porting is created equal. Some shops just sandblast the inside and call it done. That’s not porting-that’s polishing. Real porting involves:

- Measuring airflow with a flow bench before and after

- Using CAD software to model optimal runner shapes

- Matching port shapes to cylinder head flow characteristics

- Blending transitions smoothly to avoid turbulence

- Providing before-and-after flow numbers

Ask for proof. A good shop will show you a flow chart. If they say, "It flows better," without numbers, walk away. You’re paying for precision, not guesswork.

Also, check if they offer a warranty. A reputable shop stands behind their work. If your ported throttle body develops a leak or cracks, they should fix it.

Alternatives to Porting

Before you spend $1,000 on porting, consider these alternatives:

- Aftermarket throttle body: A 75mm aftermarket unit from BBK or FAST might flow more than a ported stock unit, and it’s plug-and-play.

- Aftermarket intake manifold: A performance manifold from Edelbrock or AEM can outflow a ported stock unit and come with a pre-tuned calibration.

- Throttle body spacer: For some engines, a spacer can improve low-end torque without changing airflow geometry.

These options are often cheaper, faster, and more predictable. You don’t need to wait weeks for a port job. You just bolt it on and drive.

Final Decision: Is It Worth It?

Porting a throttle body or intake manifold makes sense if:

- You’re building a naturally aspirated engine with high-RPM goals

- You’re already doing other head work (cams, valves, ported heads)

- You’re willing to spend on a proper dyno tune

- You’re not chasing low-end torque

It’s not worth it if:

- You drive mostly in city traffic

- You have a turbocharged engine without other upgrades

- You’re on a tight budget

- You’re not planning to tune the ECU

The best performance gains come from a system approach-not one part. Porting is a tool, not a magic bullet. Use it wisely, and it can give you clean, reliable power. Use it blindly, and you’ll waste money and time.

Does porting a throttle body improve fuel economy?

Not usually. Porting improves airflow for power, not efficiency. In fact, because the engine can now take in more air, it may use more fuel if the tune isn’t adjusted. Some drivers report slightly better fuel economy at cruising speeds due to reduced pumping losses, but that’s rare and inconsistent. Don’t port for mileage.

Can I port my own intake manifold?

You can try, but it’s risky. Without a flow bench and experience, you’re likely to make the airflow worse. Most DIYers remove too much material, create uneven surfaces, or mess up the runner length. Even small mistakes can hurt performance. If you’re serious, start with a cheap, used manifold to practice. But for a daily driver or expensive engine, hire a pro.

How long does porting take?

A throttle body port job usually takes 1 to 2 days. An intake manifold can take 5 to 10 days, depending on complexity. High-end shops often have a backlog. Plan ahead-don’t wait until race day to find out you’re on a 3-week waitlist.

Will porting void my warranty?

Yes, if your vehicle is still under factory warranty. Modifying internal engine components like the intake or throttle body is considered a performance alteration. Even if the part doesn’t fail, the manufacturer can deny claims for related systems if they suspect the modification contributed to a problem.

Do I need to upgrade my fuel system after porting?

It depends. On a naturally aspirated engine with minor porting (under 20% more airflow), stock injectors and fuel pump are usually fine. But if you’re seeing lean codes, misfires, or a drop in fuel trims, you’ll need bigger injectors or a higher-flow fuel pump. Always monitor fuel trims after porting and tuning.

Comments

Rae Blackburn

They're lying about the gains. Porting is just a scam to get your money. The real power comes from the government's secret air manipulation tech. You think you're getting 20 hp? You're getting mind control.

They don't want you to know this.

December 31, 2025 at 15:11

LeVar Trotter

There's a critical misconception here. Porting isn't just about increasing cross-sectional area-it's about optimizing Reynolds number, boundary layer control, and pressure gradient management. The real magic happens in the transition zones between the throttle body bore and the runner entrance. You need to maintain a 1.5:1 aspect ratio to avoid flow separation. Most shops don't even measure velocity profiles, let alone use CFD to validate their work. If they're not showing you flow bench data at 10, 20, and 30 inches of water, they're just sanding plastic.

January 2, 2026 at 07:05

Tyler Durden

I did this myself on my 2004 Civic Si-stock 62mm throttle body, went to a 70mm unit, hand-filed the throat, blended the walls with sandpaper and a Dremel... got 11 hp on the dyno at 6k RPM and zero loss below 3k. I didn't even tune it. It ran fine. Maybe I got lucky. Maybe the ECU just adapted. Either way, I'm not paying $1,200 for someone to touch my car. I'm not a mechanic, but I'm not stupid either.

January 3, 2026 at 22:56

Seraphina Nero

I just want to know if this will make my car quieter. I hate how loud it gets when I floor it.

January 4, 2026 at 22:54

Megan Ellaby

ok so i tried porting my intake once with a dremel and like... it went real bad. i took too much off and now it leaks air and my car idles like a dying cat. lesson learned: dont do it yourself unless you have a flow bench and a PhD in fluid dynamics. or just buy a used aftermarket one. cheaper and less heartbreak.

January 5, 2026 at 08:44

allison berroteran

It's interesting how we equate more airflow with more power, as if the engine is some kind of hungry beast that needs to be fed more air to be satisfied. But what if the real issue isn't how much air it can take in-but how well it can use what it already has? Maybe the magic isn't in the porting at all, but in the harmony between fuel, spark, and timing. Maybe we're chasing speed while ignoring stillness. The engine doesn't care about horsepower numbers. It just wants to breathe. And maybe, just maybe, the quietest, most efficient breath is the one we've been ignoring all along.

January 6, 2026 at 18:53

Gabby Love

The part about needing a tune after porting is 100% correct. I had a friend who ported his LS3 and skipped the tune. Ran lean under load. Melted a piston. $4k repair. Don't be that guy.

January 7, 2026 at 04:04

Jen Kay

I appreciate the thorough breakdown. It's refreshing to see someone acknowledge that performance isn't just about going faster-it's about understanding the system. That said, I do find it ironic that we're spending $1,500 to make an engine breathe better... while ignoring the fact that most people drive their cars like they're in a parking lot. Maybe the real upgrade is learning to drive slower.

January 7, 2026 at 15:27

Michael Thomas

You guys are overcomplicating this. American engines were built to run. Foreigners overthink everything. Just bolt on a bigger throttle body and drive. No tune needed. If your car can't handle it, you're driving wrong.

January 8, 2026 at 04:19

Abert Canada

I tried porting my Toyota 2GR-FSE last winter. Took it to this shop in Vancouver that claimed they "do dyno-proven work." Got it back, dynoed it-gained 18 hp at 6k, but lost 14 lb-ft at 2k. My daily commute turned into a nightmare. Had to downshift constantly. Ended up selling the car. Turns out, Canadian winters don't care about your peak power. They care about traction. And torque. Not horsepower.

January 10, 2026 at 02:36

Xavier Lévesque

So you're telling me I spent 6 months waiting for a ported intake on my WRX... just so I can feel a 20hp gain at 6500rpm while the turbo spools at 4000? And now I have to pay $800 for a tune? Bro. I could've just bought a used GT3076 and called it a day. This is like buying a Ferrari engine and putting it in a snowmobile.

January 11, 2026 at 06:06

Thabo mangena

In my humble estimation, the pursuit of incremental airflow gains through porting represents a noble, albeit highly specialized, endeavor in the broader discipline of internal combustion optimization. One must, however, exercise prudence, as the economic and mechanical ramifications may not always align with the anticipated outcomes. One might even posit that the true measure of engineering excellence lies not in the magnitude of horsepower achieved, but in the elegance of the solution.

January 11, 2026 at 16:19

Karl Fisher

Porting? Please. The only thing that gets you power is a bigger turbo. Everything else is just car guys playing with sandpaper because they don't have the balls to go full boost. And don't even get me started on the "tune after porting" nonsense. That's just the shop's way of upselling you. I've done 3 port jobs. Never tuned once. Still running strong.

January 13, 2026 at 03:40

Buddy Faith

You think porting is real? Nah. The government put a chip in your ECU that only lets you get 70% of your engine's power. They don't want you to go too fast. Porting just bypasses that. The real gains are hidden. The dyno charts? Fake. The shops? All in on the scam. I know a guy who ported his Camry and it started flying. Literally. He had to stop driving it because it kept lifting off the ground.

January 13, 2026 at 09:30

Scott Perlman

I ported my throttle body and it just made my car louder. Didn't feel any faster. But hey, at least it sounds cool now.

January 14, 2026 at 04:01